The Dogs of War

It’s fair to say that a lot has changed since 2009, when Halo Wars made its debut. It was a console generation ago, but more than that, it was another era. Halo 3 was at its peak of dominating console multiplayer. What would become 343 Industries was still forming at Microsoft to take control of the Halo franchise, and Bungie still had Halo 3: ODST and Reach to release before it would part ways with the franchise for good. Halo Wars was also very much an expanded universe-styled entry in accordance with previous non-mainline Halo games, with a story and characters walled off from what the main games was doing.

Fast forward to 2017, and a lot has changed. Bungie has moved on, 343 Industries minds the shop, and the Halo franchise is sprawling, looking positively massive compared to its comparatively tiny roots the better part of a decade ago. More importantly, 343 has long ago done away with Bungie’s arm-length approach to its expanded universe; in pre-launch interviews, they repeatedly promised that Halo Wars 2 was going to matter to the wider world of Halo.

And now, here it is.

A lot could be said about Halo Wars 2 from a gameplay standpoint, or what it does differently or the same as its predecessor. What concerns us, however, is its story. A sequel brings with it expectations—how will it improve on its predecessor, or tell a tale markedly different or fundamentally the same. And so let’s dive into the campaign and the story 343 Industries and Creative Assembly have crafted…

For those who have an interest in experiencing Halo Wars 2’s story firsthand, we recommend that you play through the campaign before reading further.

All Around Me Are Familiar Faces…

Halo Wars was in many ways a story of archetypes. Its heroes were the brainy scientist (Anders), stoic commander (Cutter), hotheaded grunt (Forge), and sardonic AI (Serina) we’re familiar with from countless action films or previous science fiction—and Halo had seen plenty of those characters before Halo Wars appeared. In opposition to these forces were the guileful villain (the Prophet of Regret) and his muscled enforcer (the Arbiter Ripa ‘Moramee.) The plot, too, was so stock to Halo it could be considered a classic trope at this point—outmatched humans fighting Covenant find a Forerunner macguffin that could tilt the tables of the war. In order to stop it from being used against them, they are forced to destroy it. In the words of Cortana, “It’s not a very original plan, but we know it’ll work.”

But to simply call Halo Wars rote formula would do it a disservice. While it dealt in tropes and familiar situations, it executed those tropes well. It also did more than its fair share of providing depth to the universe, giving us our first look at a Shield World or the battle-scarred world of Harvest. Subtle connections to previous media like the MJOLNIR-derived Cyclops were there for sharp-eyed players, as well as additional lore information in the form of the Halo timeline and “Black Boxes” scattered throughout the levels. Standout cinematics and voice acting elevated the material, and enough people ended up caring about these characters for the game to get a sequel.

In the rough outlines, Halo Wars 2 follows on in much the same way as its predecessor. Its story is not as formulaic as its predecessor, but it remains remarkably simple. The world of Halo has grown far more complex than the simple UNSC vs. Covenant of earlier games and novels, but despite working to integrate the unstuck-in-time crew of the UNSC Spirit of Fire with the current world affairs, Halo Wars 2 keeps the stakes clear, the story simple, and the cast of characters minimal.

With Sergeant Forge having stayed behind to blow up the aforementioned Forerunner macguffin of the last game, and Serina having reached the end of her useful life long ago, Spirit of Fire’s crew awakens at the edge of another Forerunner construction unlike any they have seen before—the Ark. Anders is raring to explore this new installation, while Cutter is far more preoccupied with finding out what’s been going on in the wider universe while they have been adrift for more than 20 years, as well as who plucked Spirit of Fire from its previous course and took it to the edge of the galaxy.

Here in the opening cutscene there’s a lot of quick establishing of relationships and table-setting for new players who haven’t played the original, but there’s also a lot for Halo fans to get out of it too. The lingering shot of Forge’s empty cryotube is unmissable, and even if you aren’t familiar with the role Serina played, her farewell to to Cutter by way of status update gives players a chance to see the softer side hidden behind her dry wit in the first game. The brief, casual mention of Serina a few minutes later—and the halting pause and almost guilty look from Anders—also are enough to give casual players a clear indication that whoever she was, she was important, and her absence is felt.

The plot keeps rolling, and soon Spirit of Fire is trying to find the source of an encrypted transmission from the Ark’s surface. The three Spartans Jerome, Alice, and Douglas disembark to the surface, finding the ruins of a UNSC research outpost and a logistics AI, Isabel, who warns them to leave. Investigating, the Spartans come across the Brute Atriox—and get utterly stomped.

In many ways, Halo Wars was the first game in which we saw Spartans be as fast and acrobatic and lethal as Eric Nylund’s novels had always told fans they were, and so having Halo Wars 2‘s antagonist show up immediately and seriously wound Douglas immediately sets stakes, introduces the enemy, and gives him heft. 343 has taken criticism in other media for using dead Spartans as a shorthand to demonstrate an enemy’s power—the deaths of Spartan-IVs and Black Team in Escalation being notable examples—but ending the first short mission with Douglas injured and Alice possible KIA is more effective than any of these previous character sacrifices.

On board Spirit of Fire, Isabel quickly gives Cutter and company an update on the most pressing issue—that the researchers on the Ark had their communications and portal back to Earth unexpectedly cut off, and shortly afterwards Atriox and his faction, the Banished, quickly showed up, mowed everyone down, and set up shop. Isabel’s advice is to run, but Cutter instead gives a rousing speech that despite being old and just one undermanned ship, he and his crew are ready to do their duty and stop Atriox, whatever the cost.

Launching operations to the Ark’s surface, the forces of Spirit of Fire manage to disrupt Atriox’s supply lines and control over the Ark’s teleportation nodes, finishing off one of Atriox’s lieutenants, Decimus. When Spirit of Fire comes under attack from Atriox’s air fleet, including a CAS-class assault carrier, Anders suggests using the Halo ringworld kept at the Ark as a signal buoy—launching the ring to its intended location in the Soell system, near enough to contact the UNSC in friendly space. Isabel contrives a way to get the Ark’s automated Sentinel defense forces aggravated, turning them against Atriox’s assault carrier. In a pitched battle on the Halo, Anders manages to launch the ring with her aboard, promising Cutter that she’ll bring help soon. Entrusting that Anders will manage to bring backup, Cutter and Isabel plan strategy against the Banished while Atriox plots his own next moves. And so the story ends… for now.

Heroes and Demons

As the above summary demonstrates, Halo Wars 2 keeps things simple. While the original game used established archetypes and tropes in a straightforward manner, Halo Wars 2 is a game much more aware of the universe it inhabits. In an interesting bit of meta-commentary, Anders at one point begs the UNSC not to destroy the Halo ring, in what you could consider a wink to players who have been previously frustrated by the swift introduction and destruction of Requiem and other Forerunner installations. This aware simplicity extends to the gameplay itself, which uses Blur Studios’ legendary cinematics more sparingly, spreading roughly the same duration over fewer scattered movies rather than one after every mission. Instead a lot of the game’s plot and chatter are related in pre-mission loading screen briefings, akin to classic RTS like StarCraft, and through in-game cutscenes and vignettes. While it doesn’t take this seamless approach to the level of a game like WarCraft, there’s a tangible benefit to keeping more of this stuff in-game. First off, lots of people mash the skip button on cutscenes, so this forces people to pay more attention, but it also cuts down on the usual divide between what the player can do and what the player just has to watch. It took a cinematic for the Spartans’ acrobats and combat prowess to be shown off in the original Halo Wars, but in Halo Wars 2 it’s reinforced throughout the game, such as the pirouettes and flourishes Jerome or Alice dispatch enemies with, or the impact as they leap onto vehicles for boarding. The only major flaw in this approach is the curious use of static character portraits rather than animated ones, a downgrade from the original Halo Wars that makes the game feel strangely dated and cheap in comparison.

There’s not a lot in the game that requires previous Halo knowledge, but for people who might feel lost, the Black Boxes from Halo Wars return in an upgraded form, dubbed the Phoenix Logs. Less a collection of stories and timeline, the Phoenix Logs are much more akin to a codex found in other sprawling games with deep lore, and it’s hands-down the most welcome lore addition to a Halo game in recent memory. Logs are unlocked by completing objectives in the campaign and finding scattered collectibles, but in comparison to the innocuous Black Boxes scattered across the first game’s levels, 343 and Creative Assembly opted to make the Phoenix Logs easily accessible. In the first mission, the luminous Phoenix Logs basically serve as waypoints on the map, and they show up on the player’s minimap as well. Without trying to hard I got more than two-thirds of them on my first play through of the campaign, and diligent players could easily pick up more without too much effort. While this might be a slight disappointment to people who like scouring the map for hidden secrets, it’s a clear lesson learned from previous Halo games where important supplemental knowledge was locked behind terminals and external material. If you want to know what each building of your base does or more about the characters you see on screen, the Phoenix Logs supply plenty. I sincerely hope 343 looks towards this and previous efforts like Combat Evolved Anniversary‘s Kinect-only Library feature and makes some equivalent in every game going forward; it’s a simple way to help players catch up on the sprawling world they jump into with every game.

The Phoenix Logs also offer a great opportunity to dive into aspects of the canon that don’t really merit being part of the main story but still enrich it, and they absolutely capitalize on the opportunity. Inside the logs, we get tidbits that demonstrate the horrifying brutality of the Banished—such as the regular execution of panicky Unggoy, the premature death of the Lekgolo worms that pilot Atriox’s Scarab platforms, and that the Engineers the Banished enslaved are tortured endlessly by the Ark’s requests for repairs that they cannot answer. The logs and the game itself also capitalize on small tidbits of established lore rather brilliantly, such as Anders using the Halo’s ability to selectively vent portions of the ring into space, first since in a Combat Evolved Anniversary terminal as 343 Guilty Spark frittered away his time in isolation. Details from Halo: Reach make appearances (the Banished’s cloaking tech was reverse-engineered from the Covenant Pylons used to hide Covenant ground operations in the battle for Reach) as does Karen Traviss’ Kilo-5 Trilogy (with the outlying human outlaw planet Venezia being a prime spot where Atriox bolstered his munitions and technology post-war.) The fallout from Hunters in the Dark is the subject of some sadly poignant journal entries from Nathan Palmer, an archaeologist at the Henry Lamb research outpost who marvels at the ability of the Ark to repair itself, and then faces a bleak fight for survival after the Banished destroy everything. Even the Librarian’s plans for humanity to inherit the Mantle are discussed briefly by Anders, who understandably is a bit creeped out by the level of control she desired and likens humanity to the fossilized creatures in amber they find on the Ark.

Even with the Phoenix Logs, another key strength of Halo Wars 2‘s campaign is that it doesn’t lean heavily on them. While fans of the series will automatically know what the Ark is and its significance, it never assumes that knowledge is a given, and it doesn’t dwell too much on the history outside of the Logs. Basically the only knowledge someone would need to understand the game’s story is that previous games had humans in ships fighting aliens. It’s a very low bar to clear, and is generally to the game’s benefit.

I say “generally” because there are points where that focus on a streamlined story sometimes skips over spots that could use elaboration. Two-thirds of the way through the campaign, the plot point that the Ark creates Halos comes out of nowhere if you’re a casual player, and more pressingly, no one on Spirit of Fire seems all that surprised by the revelation. The implicit assumption is like much of their information (such as the fate of the Master Chief, the end of the Human-Covenant War, and how the UNSC came to find the Ark) Isabel related it off-screen, but it shortchanges new and returning players of some payoffs. Until the events of the first mission, Cutter and the crew of Spirit of Fire thought they had encountered truly novel circumstances, fighting a terrifying alien parasite on a fantastically impossible artificial world. Now they are thrown into a setting where the Forerunners are a known quantity and the shield world they blew up is a tinker toy compared to the size of some Forerunner installations.

Likewise, fans are robbed of some pretty large character moments, especially regarding Spirit of Fire’s crew. In the Halo Wars timeline, a particularly poignant entry notes that en route to the shield world, Serina forges letters from home for the crew, on the assumption that their hasty pursuit into uncharted space might end with none of them getting back to their families. It’s not only a brilliant character point for Serina, but it was one of the few elements of the first game that focused on the everyday crew. Cutter’s speech to Isabel outlining why they are not going to run specifically brings up the crew again, and the cinematography follows the bridge crew as they listen—but we don’t get any further examination of what that means. The arrival of Spirit of Fire in the modern world, a world that regarded them as lost, and world where their old war was already won, was a chance for a lot of pathos. What must it feel like for Cutter to know that his wife and children have aged without him, growing old or possibly even dying? That Reach, the place thought safest in the galaxy, fell to the Covenant, and that his friends might all be among the millions of dead in the wake of the war with the Covenant? From his speech, we can infer that he has focused his attention to his crew as surrogate family, but all we get is a rousing speech—it’s never brought up again, save for a stray mention in the Logs. The reason may be a desire to keep things light and not focus on the events of the first game to avoid alienating new players—but as a result, we lose a chance to learn more about these characters.

The missed opportunity of Spirit of Fire‘s homecoming is compounded by the fact that most of the recurring characters get very little screen time. Anders and Cutter both have flashes of dialogue that suggests how they might have changed since the first game, but it’s never explored; the repercussions of the events of the first game are covered more in the original game’s post-Halo Wars timeline entries than in the entirety of the follow-up game. Instead, they mostly remain in their archetypal roles, with Anders figuring out a technical solution and plumbing the depths of Forerunner relics, and Cutter being command material.

Surprisingly, the only returning characters who get any major added depth in Halo Wars are the Spartans. In the first game, Red Team were basically just hero units with different guns and voices. In Halo Wars 2, though, far more time is spent with them, and their Phoenix Logs give full backgrounds of their early lives. Interestingly, Jerome, Douglas, and Alice were all Spartan-II washouts, and their backgrounds pre-induction and their difficulties or ease in integrating with the rest of the Spartans are detailed. More than just operating as a well-oiled machine in the first game, their personality and camaraderie gets arguably more screen time than Blue Team’s in Halo 5.

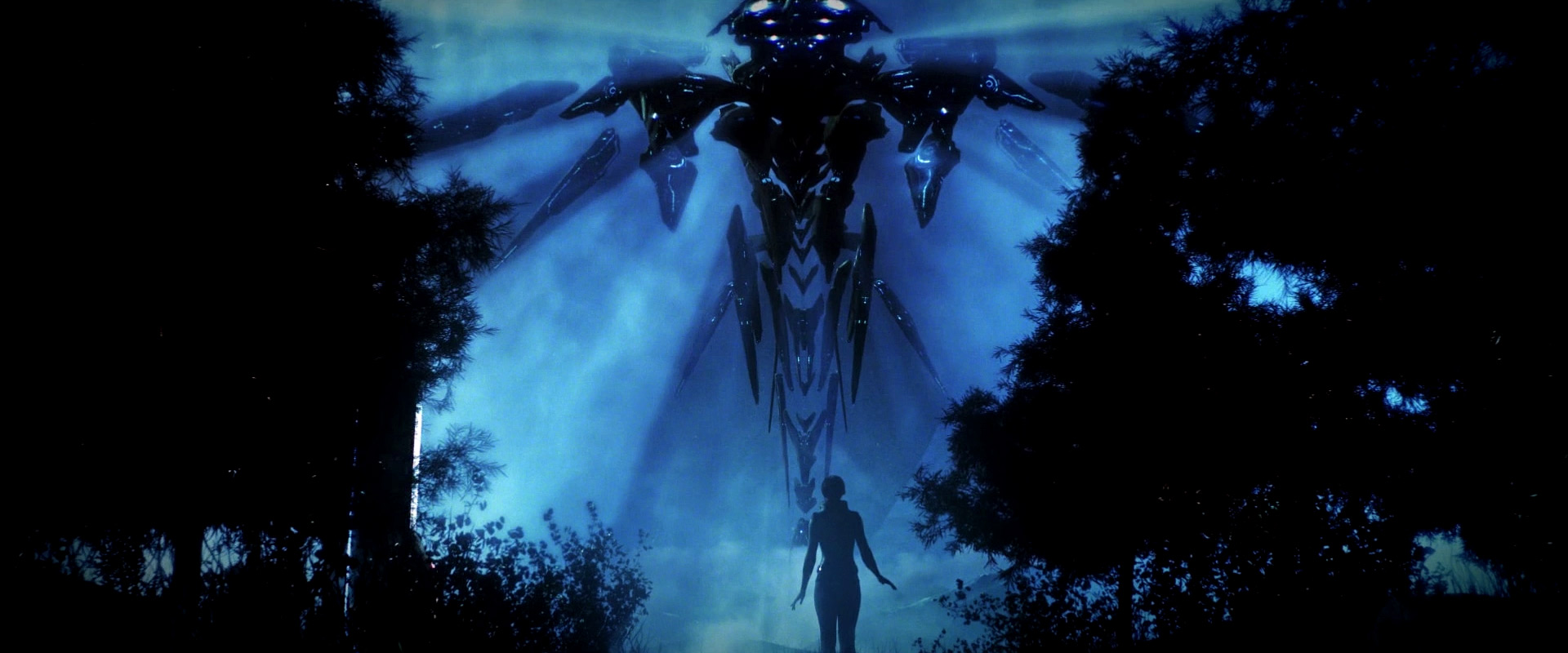

While the fleshing out of Red Team is excellent, none of the above-mentioned characters have an actual character arc in the game. The one to receive that benefit is newcomer Isabel. AIs in Halo have always been a study of contrasts, and where Serina was basically Cortana with the snark and sarcasm meter tuned up to 11, Isabel comes off as far more human, alternating between being terrified, angry, and vengeful. She and Jerome form a working relationship during the game that strikes one as awfully reminiscent of the Master Chief and Cortana in the first Halo games, and it’s a welcome dynamic to return. By the end of the game, Isabel has proven herself a valuable addition to Spirit of Fire, but in destroying the assault carrier Enduring Conviction she also gets a measure of revenge against the Banished for the death of her human charges; as she infiltrates the assault carrier in a visually stunning cutscene, we get snatches of her remembering the distress calls sent by the doomed humans of her research camp, and get a brief taste of just how much her failure to protect them weighs on her.

Breaking Stuff To Look Tough

No story can be great without proper antagonists, as Halo Wars 2 writer Kevin Grace points out, and 343 spent a lot of time building up Atriox as Halo‘s new Big Bad. Introducing the Banished as a shadow group in opposition to the Covenant even before the Great Schism at first blush presents some series lore issues, but to 343’s credit the integration of the Banished is remarkably clean, and in fact answers some lingering questions posed by previous universe material, most prominently in Halo Wars. When Regret mentions that the war against humanity requires more war machines that the Covenant can currently field, Ripa ‘Moramee brazenly says that he will take what they have to destroy the enemy—to which Regret rebukes him, saying that to do so would leave them “defenseless”. Until now, it’s been an open question of what the Covenant could have possible been defenseless against besides humanity, but the Banished can clearly fill that role. Likewise, the posting of an entire fleet led by the revered Sangheili general ‘Jar Wattinree to the fringes of Covenant space in the middle of the war with humanity seems odd, unless Wattinree was there to ward off the Banished—certainly the Prophets would not have given such a dangerous Elite his own fleet unless it was necessary for his campaign.1 The Phoenix logs also reveal that ONI slowly became aware of Atriox and the Banished in the closing stages of the Human-Covenant War, and watched as the discord sown by the dissolution of the Covenant offered him a chance to grab more materiel and persons to his cause.

But while 343 has effectively managed to build up the Banished as a successor to the Covenant, Atriox and his lieutenants ultimately don’t live up to their reputation. In a lot of fiction, the best antagonists are a warped mirror version of the protagonists, and on the surface, Atriox seems to fit the bill. There are parallels to be made between Cutter and his focus on his crew and the choices Atriox and his brethren made to form the Banished, particularly with Shipmaster Let ‘Volir’s decision to accept the ridicule and hatred of his Sangheili brethren to become a hired gun for a Jiralhanae. But this is never explicitly drawn out in the game.

More to the point, as much as is made of Atriox’s multitudes—his tactical cunning great enough to avoid being destroyed by the Covenant at his height, his diplomacy great enough to convince Let ‘Volir and even a squad of Sangheili assassins to forsake their previous animosities and join him—really only his bestial strength comes through in the game proper. Cutter and Spirit of Fire come in to the nice setup he has created and wreck it entirely, without ever really suffering anything but minor speed bumps along the way.

More distressingly, not much comes of the fight between Atriox and Cutter as commanders. For most of the game, they never talk to each other at all, and by the end Atriox is mostly sniping at Cutter, and Cutter is responding (reasonably) that there’s no way in hell he’s gonna’ trust a damn dirty ape. This seems true to Cutter’s character and his experience with a Covenant that takes no quarter, but it doesn’t exactly generate any explosive antagonistic chemistry on screen. That the characters never meet doesn’t matter much—Captain Kirk and Khan Noonien Singh never have to be in the same room as each other in order to electrify the conflict at the heart of Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan—but that they never really argue about anything of substance does. The “Know Your Enemy” live action shorts 343 released in advance of the game’s release have more substance to them than the game itself. Rather than coming to a head, the showdown between them just ends. The game also poses questions that it never answers, such as just who actually did pluck Spirit of Fire out of deep space and take it to the Ark? Anders’ surprise run-in with a Guardian combined with the Legendary ending of Halo 5 suggest that Cortana may hijack the replacement Halo for her own purposes, but we’re left with very little to base firm conclusions on. Taken together, the game feels like it ends of a cliffhanger, and one that personally comes off as less satisfying than Halo 2‘s much-maligned ending.

The benefit to all of these shortcomings of the game is that they may yet be redressed. Halo Wars 2 will be the first Halo game to have post-launch campaign DLC, and it might take the first steps towards integrating the events of Halo Wars 2 into the wider Halo universe. Cortana and the Created have assumed the Mantle and massively upset the balance of power in the galaxy, and learning how those events factor in to what happens on the Ark will be exciting. Likewise, there remains and opportunity to flesh out Cutter and Atriox as characters, and their conflicts, and (perhaps) make more of the Ark’s setting. After all, there remains a buried Mendicant Bias somewhere on its surface…

In conclusion, Halo Wars 2 feels like a worthy successor to the original game, and it also works as a welcome introduction to the universe for newcomers, as well as providing more for dedicated lore fans to sink their teeth into. Its biggest weakness is that it ends with unfinished questions and an unfinished story. It leaves you wanting more; all things considered, though, that’s a credit to what’s already there.

- H/T to Harupsis over at Halo Archive for this insight: http://www.haloarchive.com/forum/topic/1107-halo-wars-2/?do=findComment&comment=220250 ↩