Nine Levels Underground

Nine Levels Underground

(Hell and Humanity in Halo 3: ODST)

1. Transport for One

Looking down the assembly line of shooters, it can sometimes be hard to hold out hope for the genre, at least in narrative terms. The modern shooter, be it first- or third-person, is cut from the same cloth that furnished the halls of Doom, a game in which your featureless protagonist slaughtered wave after wave of hellish or alien foes until the credits rolled. But while that basic fabric may have satisfied in the halcyon days of sprites and keycards, it has grown threadbare with the increasing scale and fidelity of our videogame experiences.

The biggest shooter franchises today are still obsessed with the extraterrestrial enemy, or at least the subterranean one: Gears of War has its Locust, Half-Life its Combine, Killzone its Helghast, Resistance its Chimera, and Halo its Covenant (and Flood). In the few cases where our shooters stay grounded, granting us combat against our own species, the experience centres either around Hollywood-stock “shocks” (Call of Duty), or muddled amorality (Far Cry 2). For the most part, it is the generality of ‘mankind’ that our games are concerned with – a sanctified mankind always on the brink of extinction, forever facing a threat that is entirely other, that can happily be dispatched without qualms or doubt. And so we are left in a kind of limbo, recast again and again in the same old role as saviour of the human race. Meanwhile, this role grows less affecting over time, especially when these games seldom present a generalized humanity that would be worth saving at all.

Of course, videogames should be their own reward; as any forum-dweller will tell you, it is gameplay that matters. On this view, to ask how institutions such as the Interplanetary Strategic Alliance (ISA) in the Killzone games or the United Nations Space Command (UNSC) of the Halo universe represent or reflect mankind as we know it is to miss the point, or at least to stray from it. But it is impossible to tell a story in any medium, no matter how tawdry or inconsequential, without staking out positions and perspectives, even unintentionally. Everything you show your audience is saying something, and your intricate, fictional systems of galactic governance, whether you realize it or not, tell us not just what you believe the future of mankind to be, but what you value of our present. Right now, what videogames say about us as a species is that we are regimental warmongers, and that our lives are nasty, brutish, and short. In the case of the Halo series, it could be said that we also enjoy sassy one-liners. Perhaps our games are not wrong.

The world of Halo, however, is peculiar, and peculiarly successful: it is often bright, colourful, and comical, brimming with good humour and camaraderie. That same colour and comedy, coupled with curiously durable mechanics, has aided and abetted its reputation as the ‘kiddy’ FPS, and yet Halo is perhaps the most sophisticated of all the shooters mentioned above in terms of world-building. For a game that began as a derivative amalgam of other science fiction, principally Larry Niven’s Ringworld and the Alien movies, Halo has grown surprisingly broad, and the range of material ancillary to the games – novels, comics, short films, even an encyclopaedia – is testament to a universe that is proving perfectly mutable.

The transition from single game to world-dominating franchise has not always been kind to Halo, however, and the first game’s sequels are blighted with customary problems of storytelling caused by the swelling universe. The pacing and plotting of Halo 2 and Halo 3 are clunky at best, betraying the increasing complexity of the background story, much of which is told through a parallel series of novels, but all of which needs to be clear, or at least decipherable, to the first-time player. By the end of Halo 3, Bungie were expected to tie multiple story strands off, all the while dodging problems of continuity and canon raised by the mountain of supplementary books, comics, ARGs, and tie-in Mountain Dew.

As Marcus Lehto put it in an interview with Edge:

“It was a true burden for us when we were making those games, because we sometimes wanted to do something but couldn’t because the story wouldn’t let us, or we had to support this giant steamroller of a story.”

It takes careful attention to the Halo trilogy, together with some often lacklustre extracurricular reading, to make total sense of the ravelled and often confusing tale told in those games. Even then, some of Bungie’s best storytelling is done off-stage: the Terminals of Halo 3 reward the diligent player with a frame narrative that elegantly recasts the events of the trilogy as the resolution of an eons-old conflict between Forerunners and Flood. Most of us missed it, however, and thanks are still due to the staff of Ascendant Justice, then and now, for their efforts in bringing it to our notice.

Another problem often documented, and more widely felt, is the sterility of the Halo universe, at least as presented in the games. While it is hard to fault the “30 seconds of fun” mantra that is at the core of the Halo gameplay experience, the series has been routinely criticized for the duplication of its environments, and for the “backtracking” through these that is required to progress. The first game, set almost entirely on a verdant if lifeless Halo installation, was ideally suited to Bungie’s repetitious design philosophy, with only a few levels (foremost among them being ‘The Library’) singled out for their over-familiarity. The problem became more apparent when we briefly visited Earth in Halo 2, and again in Halo 3. In both cases, these Earth levels had been advertised as being the central experience of the game, and yet in both titles the player’s eventual destination would prove to be an abandoned Forerunner relic in some distant corner of the universe, far from any humans not kitted out in combat gear, and immeasurably removed from any climactic battle for the fate of identifiable men and women, if not ‘mankind’.

A generous quarter of Halo 2 is set in the streets of New Mombasa, the only human city we have yet to visit in a Halo game, and those levels pale in comparison to an early trailer showing large-scale urban combat. Halo 3 keeps us on our home planet a while longer, but presents us solely with rusted military bunkers and a few factories. At no point does Bungie’s Earth convey a sense of human life and living; the environments in Halo 2 and Halo 3 are missed opportunities to show us homes, restaurants, concert-halls, train stations, and the people who frequent them, the people we are allegedly fighting for. To play the Halo games without ever consulting the series’ supplementary material is to never know which or what ‘mankind’ your avatar, the Master Chief, has sworn to protect. In the Halo trilogy proper, life in the 26th century is an elision. To compare it with Bioshock – a shooter at the other end of the spectrum in terms of conveying a detailed understanding of people and their daily living – is laughable. Gears of War, for all the savagery and baseness of its vision, gives us genuinely human environments, now ruined and destroyed. Even Valve’s take on the world ravaged by the zombie apocalypse of the Left 4 Dead games is more human than Halo 3‘s hard-hatted factory workers, the only civilians we meet in the latter game. When Lord Hood informs Rtas ‘Vadum that he “glassed half a continent”, his words have no weight, because as far as the unthinking player is concerned, that ‘continent’ is just a few abandoned warehouses slumped on the lip of a dustbowl.

Bungie have made much, at times, of the relationship between the player’s avatar, Master Chief, and his sentient AI companion Cortana. That is to say, the central human relationship of the Halo trilogy is between a near-silent, genetically-engineered soldier – and a hologram. Master Chief never speaks in-game, saving his few gruff (and alienating: contrast Bungie’s use of the ‘faceless’ protagonist with Valve’s consistently silent Gordon Freeman) one-liners for the third-person cutscenes that carry most of the water for the series’ story. These short sequences between levels are often asked to do too much work in too short a time, however, and the result is that the narrative piles up behind them like the carriages in a train wreck. The mounting convolutions of the Halo trilogy’s plot require its protagonist to be ferried around the galaxy at speed, and the games’ cutscenes usually slave to make these transportations clear, leaving few opportunities for them to deepen our immersion in the universe, or even to make plain the motivations of the various characters and shifting factions. More importantly, they can’t convince us to care for a humanity that is all but absent from the world of the games. And while the conclusion of the trilogy is a shaky triumph in pure plot terms – pulling free, in the end, from its downward spiral of exposition, albeit with a few flourishes that have more in common with skilful conjuring than good writing – it is a triumph that rings largely hollow.

2. Hope Station …

Bungie’s latest title, Halo 3: ODST, is a prequel-cum-expansion that aims to make explicit a piece of story as yet untold in the universe, concerning a small squad of Orbital Drop Shock Troopers deployed in an occupied New Mombasa, following the slipspace jump the Prophet of Regret initiated over the city during Halo 2. It promises much for devoted fans of the series: a return to many of the mechanics of the original Halo: Combat Evolved, including health packs and a reinvigorated pistol; a focused story, relatively small in scale, no longer tethered to the galaxy-hopping sprawl on the trilogy proper; and a newer, darker tone, reflecting both the vulnerability of the Troopers as compared to Master Chief, and the game’s core setting – a ruined, human city.

This tone is apparent as soon as the disc loads: the Bungie logo appears among slate-grey clouds and flashes of lightning, and the game is boiler-plated with a further situational blurb, drawing on typical videogame rhetoric:

“The year is 2552. Humanity is at war with an alien alliance… We are losing. They have burned our worlds, killing billions in their genocidal campaign … Earth is our last bastion.” [all emphasis added]

Complete with its rising score, this introduction comes to seem superfluous with play, because Halo 3: ODST, for all its moments of pomposity and fist-pumping action, is not a game playing to the grandest scale, nor is it about humanity as a whole. No, it is a surprisingly lonely experience, one that presents a sometimes touching story about isolation and the challenges of communicating with others. If nothing else, it is diametrically opposed to the trilogy proper: if the first three Halo games gave us the ascent of the messianic Master Chief, then ODST provides a short, sharp drop for a few men (and one woman). This isn’t a story about saviours; it’s about the damned.

3. One Lost Soul

Halo 3: ODST begins with a ruinous fall: the slipspace rupture of the Prophet’s carrier causes the squad of plummeting ODSTs to scatter, crash-landing across the city; the player’s principal avatar, the helmeted, speechless ‘Rookie’ is separated from his team, and lies unconscious in his pod for some six hours. He finally comes to after nightfall, finding himself lost and alone in the newly-evacuated New Mombasa, with only hostile alien patrols for company.

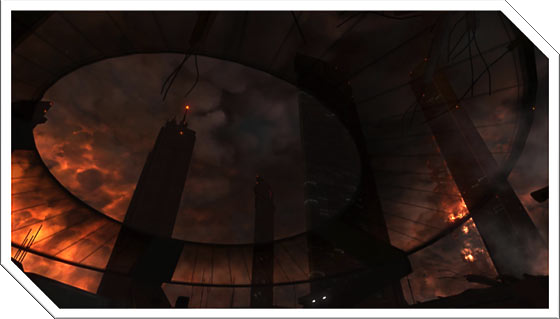

The player’s first real action in the game, once they have calibrated their thumbsticks, is to fall a second time, this time from their pod to the street below. This fall hurts: the screen flashes red, the Rookie gasps in pain, and we are prompted to scavenge around for health. Perhaps too much is made of the difference (or the lack of difference) between how the Rookie plays compared to the Master Chief, but this first display of vulnerability is striking. We are injured, and alone. New Mombasa is dark, lit only by cold neon, a blood-red sky, and occasional flashes of lightning: the city is damaged, on fire, and even the weather is against us. Although the VISR built into every ODST’s helmet helps us find our way, we are initially rudderless, unsure where to go. Even with the VISR on our prospects are gloomy, and with it off the atmosphere is suffocating. For almost the entirety of the Rookie’s experience in ODST, the sky is close and clouded, cluttered with the thickets of looming skyscrapers. If there was any doubt, we are trapped down here.

After a few preliminary skirmishes with Brutes and Grunts, help arrives in the form of the city Superintendent (an artificial intelligence responsible for the smooth running and well-being of New Mombasa). A phone rings. We answer it, using the authorization of Captain Dare, the ONI officer overseeing our mission, and a password – ‘Vergil’. The name is familiar to any Classics student, who will recognize it as the anglicized and more famous form of Publius Vergilius Maro, a Roman poet best known for The Aeneid, his attempt give the Roman people an epic to rival Homer’s Illiad and Odyssey. Vergil is also famed for his appearance in another poem by a writer of Roman descent: in The Divine Comedy (the Italian title of which is La Divina Commedia), he guides the poet Dante firstly through hell, Inferno, and on through purgatory.

At the beginning of Inferno, the first cantica of The Divine Comedy, Dante awakes from a long slumber to find himself utterly alone in a dark wood, having lost the “straight way” [diritta via], a complex notion that incorporates moral incertitude and possible alienation from God, in addition to the literal sense of being lost. Once he meets Vergil, they pass together through the gate of hell, which bears this inscription: “Lasciate ogne speranza, voi ch’intrate.” In English, this is perhaps the best known line from the poem: “Abandon all hope, you who enter here.”

In Halo 3: ODST, the Superintendent, ‘Vergil’, guides us toward a door in the side of a nearby building; he does this in a primitive but affecting way, by switching on street signs that direct us to take a “Detour” and “Keep Left”. The building’s interior is dark, but with the VISR on we can discern some graffiti on its walls (one of the few, fairly limited ways Bungie try to lend greater character to the environments of New Mombasa). It is impossible to miss one hasty scrawl in particular: “Hell on Earth” is plain to see, and to understand. Bungie may have dropped us in a human city, but it is one clearly vacated by living souls, home now only to the demonic Brutes. Figuratively speaking, we aren’t on Earth anymore; we are in hell.

Vergil leads the player up into another building, where we find Captain Dare’s cracked Recon helmet lodged in a shattered video screen (during our descent from orbit, we see Dare, the aforementioned ONI operative, wearing it on a screen in our pod). Examining her helmet now cues the first of the game’s six flashbacks, and the end of this first level, ‘Prepare to Drop’. Taken together, these seven levels and an interwoven eighth (‘Mombasa Streets’) suggest that ODST climaxes on its ninth level, ‘Data Hive’, which is also its figurative and emotional core. A tenth stage, ‘Coastal Highway’, is concerned with the team’s escape, and with their eventual ascent to safety. For the time being, however, the Rookie has no word or sign from the other ODSTs, and has to make do with piecing together what has happened over the preceding hours from a few scattered clues.

4. Five Seats

The first of the game’s flashbacks puts us in the boots of Buck, the ODST’s leader, as he pulls himself free of his crashed drop pod. This cutscene is foremost concerned with setting up our goal for the next segment of gameplay – the rescue of Dare from her own jammed pod – but it also helps to unpack a relationship Buck once had with the ONI operative (whom he touchingly calls by her first name, “Veronica”). The exposition is a little forced, but the dialogue itself is well-written, in that it is convincingly halting and incomplete. Throughout the game, Buck and Dare will squabble and struggle to speak openly with one another in this manner (although in this scene their efforts are hampered in part by of a poor communications channel). These are surprisingly human exchanges for Bungie, and mark one of the first examples of the game’s obsession with fallibility, and particularly failures in speech. Consider this: the game’s opening ‘shot’, which repeats on the game’s menu screen, is of the Rookie brooding in silence.

It is the Superintendent, Vergil, who is the game’s principal character in this regard, however: unable to speak to us directly, he can communicate only through a limited vocabulary of instructive municipal soundbites and recorded conversation. When directing us down (we are descending, remember) to Dare’s pod, he offers us this helpful snippet: “Attention traveller, lost items can be claimed on lower level.” As the Rookie, of course, we have already seen his other method of guidance in action, and he will continue to activate street signs and set off car alarms throughout the game to alert the player to items he thinks may be of interest. ODST is full of characters who cannot quite get themselves across, who have to fight to make themselves understood (or, in the case of the Rookie, are entirely without a voice), and Vergil is in a sense their arbiter, trying to reunite the game’s human characters, to help them overcome their differences and the distance between them, and to guide them safely through their night in the hell New Mombasa has become.

Even the city itself has things to say to us, albeit in similarly oblique ways. In keeping with Bungie’s interest in Dante’s Inferno, the environment is littered with circles: everywhere you look, you will find street signs, patterns, plazas, corporate logos (the prime culprits being Optican, Vyrant, and Traxus), and incidental textures that either depict concentric rings or are circular themselves. Even Vergil’s icon is composed of circles, just as Dante’s hell is. At a stretch, we can find other links to Inferno, too. The first flashback of ODST takes place in an area (to the southeast of Tayari Plaza) where the walls are painted everywhere with the number six, to the point of being unsubtle. This could be seen as irrelevant, were it not for a brief exchange between Buck and Dare about the bodies of dead Elites the former finds littering the ground. He calls it a “family feud”, but those of us who played Halo 2 know the truth: the Elites have been killed because of a heretical schism within the Covenant. The circle of Hell reserved for heretics, incidentally, is the sixth. It is not known if Bungie intended all of these allusions, but once the player is on the lookout for them, they are seemingly to be found everywhere.

Buck soon reaches Dare’s pod, only to discover it now empty, and is then confronted by an alien Engineer clutching her helmet. The Engineers are a new addition to the FPS games, having only appeared previously in the novels and the real-time strategy spin-off Halo Wars, and are vital to the plot of ODST. Buck is ‘rescued’ from this encounter by Romeo, the squad’s sniper, who is at first eerily silent – until Buck remembers he will have to rescind the “standing order” he gave the smart-mouthed sniper to shut up in the game’s introduction. This is a further example of the vagaries and difficulties of communication, and is shortly followed by another, when Romeo asks Bucks if Dare ever told him what she wanted (i.e. what their mission objectives were to be). “No, never,” the Gunnery Sergeant replies, but only he (and the player) know this answer to be double-edged. In the next flashback, we hear Dutch, another of our squad members, asking his God in the aftermath of a dramatic crash landing if he will have any more flying to do today; when this question is followed immediately by an unanticipated explosion, Dutch asks “Is that a yes or a no?” All conversation in ODST, even prayer, is an uphill struggle. (The answer to Dutch’s question, as it happens, is in the affirmative, but it is surely no coincidence that this game, linked as it is with one of the great works of religious poetry, is also the first Halo title to give us a character with explicit religious beliefs.)

Thus the secret and oh-so-vital mission promised by the game’s introduction has already been sidelined; Romeo asks if we’re “popping smoke” on it. For almost the rest of its length, ODST becomes an ostensibly smaller game, with smaller concerns: getting in touch with the other members of our squad, puzzling together their night in New Mombasa through flashbacks, and getting out alive. This is quite a change from the galaxy-spanning conflict and high drama of the Halo trilogy proper, but the narrative drive of ODST is all the more affecting for it. When we return to the Rookie, emerging from the building into the Plaza area we just witnessed through Buck’s eyes, it could be considered typical Halo backtracking, but this is six hours later, six hours lonelier, and that shift in time and tone presents us with a rich interrelation of environment and story rarely felt in this series of games, and presents it in ways that are more intimate, more human, than ever before. The five men we control over the course of ODST feel similarly fallible, and yet different, because they have distinct characters (even if these, sadly, draw on typical action hero archetypes: most notably Romeo as the cocky sniper), and because we hear all but one of them speak even as we are looking through their eyes. That one exception, of course, is the Rookie, who never intrudes on his role as the player’s avatar. On the whole, however, your squad in ODST speak to one another, and to Dare – often to fire off wisecracks, but also to express worry or vulnerability. That is, they feel like they belong on the streets of New Mombasa, a human city, even if that city is now only a desolate hell.

(Of course, the New Mombasa in which we actually spend our time as players is composed in the main of a few quite similar-looking streets and buildings. This is largely a result of the night-time city being roughly mirrored across an axis, like the wings of a butterfly; if there seems like a great deal of repetition, it’s because there is. Although this should evidently be attributed to the short development cycle (and small team) that gave birth to the game, it also renders the city a reflective – and claustrophobic – maze of streets and circular plazas, reminiscent of the Amsterdam in which Camus set his novel La Chute. The concentric canals of that city, according to the narrator Clamence, resemble the circles of Hell, and the English translation of La Chute is The Fall. We shouldn’t excuse the repetition of the New Mombasa in ODST, but it is easy to explain it, and its labyrinthine streets, so easy to get lost in, also contribute to the game’s theme of hellish isolation.)

5. Good Communication

Upon retaking control of the Rookie, the player will likely stumble upon an audio log for the first time soon afterwards. There are thirty of these to be found in total, divided into nine “Circles”, and achievements are unlocked for their discovery. Developed by Fourth Wall Studios in conjunction with Bungie, the logs tell us ‘Sadie’s Story’, a narrative that interweaves with the main plot of ODST, and serves to flesh out life in New Mombasa during the first stages of the Covenant attack. To date, this is the most ‘human’ piece of storytelling in an actual Halo game, centred as it is on a young woman, Sadie Endesha, and featuring characters drawn largely from the civilians, and civil police, of New Mombasa.

Unfortunately, ‘Sadie’s Story’ is no substitute for actual contact with civilian life in-game, and at times it seems to take place in a very different and more lifelike New Mombasa; it is almost as if the (somewhat cartoonish) cast of this sub-drama were quickly ushered offstage and the set scrubbed clean ahead of the Rookie’s arrival in the city. The streets we walk and fight through are lifeless and pristine, offering only a few corpses and abandoned cars as evidence of the chaos and conflict that is meant to have just taken place. Even during the daytime flashbacks, there is no sight or sign of civilians, of the thousands of people who once populated this part of the city. Again, this can be attributed partly to the short development time and limited resources Bungie had to devote to ODST, but it is disappointing nonetheless, and a further reminder of how they have failed in their games to make actual humans, and even an idealized ‘humanity’, matter.

Where ‘Sadie’s Story’ succeeds, however, is in its thematic richness, in its recasting of Inferno. The references to Dante’s work are too numerous to detail in full, but the following commentary will suffice to demonstrate the intricacy of Fourth Wall’s story, and to cast light on the (surely intended) central themes of ODST.

Sadie, like the Rookie, is going through hell. In the first Circle of audio logs, she boards a train, number 14, hoping to enlist in the UNSC. Leaving aside Bungie’s love of the number seven and its multiples, The Divine Comedy was written in the fourteenth century. When asked for her destination, Sadie notes that, if caught, she will be in “hell” – just before (a friendly) Vergil apprehends her. This is the first of many such references: in the second “Arc” of this circle (each Circle is divided into three Arcs, save for the ninth, which has six), just after Vergil says they are departing “Hope Station” (abandoning it, you might say), Sadie tells him to go to hell; when interrupted by the sound of a slipspace rupture, she observes: “Hell just came here.”

In Circle 1, Arc 3, we are introduced to Sadie’s father, Dr Endesha. Her attempts to get and stay in touch with him throughout the audio logs – as well as her attempts to interact with and understand a varied cast of human characters – will constantly reinforce the themes of communication in ODST. But Dr Endesha is far away, “nine levels underground”, in fact, just as Dante’s vision of hell was made up of nine descending circles. Slightly more tenuous, perhaps, is a link we could make between the scientist Endesha and the learned non-believers like Aristotle who Dante says populated Limbo, the first circle of hell.

The identifications between the circles of Inferno and the Circles of the audio logs are usually more explicit than this. Circle 2, for instance, is largely concerned with the unwanted advances NMPD Commissioner Kinsler makes toward Sadie in the back of a police car, and then the sexual tension between Sadie and her rescuer Mike Branley – all of which is appropriate when we consider that the second circle of Dante’s hell is reserved for the lustful. In Circle 3, while walking through Old Mombasa, Sadie meets Jonas, a giant, corpulent butcher, self-confessedly an “800-pound man”, who is giving away his food to the refugees. Feasting constantly on his own kebabs, Jonas is the thinly-veiled personification of gluttony, the sin that consigns us to the third circle of hell. It is worth noting that Sadie abstains from eating, and that she also offers to have Vergil summon an Olifant – a garbage truck – to lift Jonas out of the area; in Dante’s Inferno, gluttons are forced to live in a filthy slush, signifying the “garbage” they have made of their lives. This is a typical example of contrapasso, a concept repeated throughout Dante’s work, where the punishment reserved for sinners in hell befits their crimes in life.

The fourth circle of hell is associated with avarice, greed, and material gain, and appropriately begins with Sadie reaching a casino, “down by the river” (this is perhaps a dual reference pointing toward the river Styx, which in Greek mythology, and in Dante’s work, flows through hell). Here she contacts her father through a bank machine. There are looters everywhere, hoarders and squanderers, and Sadie is confronted by a miserly crone who plans to break into the ATM she is using. The old woman’s efforts cause the machine to topple over, crushing her beneath it. In Inferno, meanwhile, the greedy souls of the fourth circle are made to joust one another holding great weights.

The connection with the Styx continues in Circle 5, where Sadie pushes through “panicked mobs” on a bridge above the river: the wrathful, who occupy the fifth circle of hell, were sentenced to squabble forever in the swampy waters of the Styx. This Circle also features an angry Kinsler espousing his philosophy of escalation, responding to Mike Branley’s earlier punch by bringing along a submachine gun. His ‘punishment’ is to be buried under a tide of garbage from a Vergil-controlled Olifant, just as the sullen in Inferno were buried under the marsh.

The sixth circle of hell, as mentioned earlier, is reserved for heretics, who were imprisoned for eternity in fiery, smoking tombs; it may be too much of a stretch to link this with the beginning of Circle 6, which sees Sadie and Mike trapped in the belly of a stinking Olifant. A further stretch, if we loosely map the order of the in-game flashbacks over the circles of hell, is that the run-up to the sixth ‘level’ (the fifth flashback) of ODST has us confront the fiery, still smoking ‘tomb’ of the ONI building. The flashback prior to this, coincidentally, had us blow up the bridge leading to this Alpha Site, dumping a large number of wrathful Covenant in the water below. Again, Bungie may not have intended these connections in ODST, and a consistent scheme cannot quite be drawn, but it is hard to ignore the persistent echoes of Dante’s Inferno if you keep the poem in mind while playing.

Circle 6 has more to offer on the theme of heresy, however: not only do Sadie and Mike encounter Tom, a salesman who tries to negotiate with the Covenant (this act of deviation, itself another example of attempted communication, fails horribly), but in Arc 2 we listen to Dr Endesha as he describes the actions of the heretical Engineers who are repairing damage to the Data Hive beneath the Alpha Site. Six of the Engineers give their lives to free a seventh from its explosive armour, and it is this newly-freed Engineer who will later merge with the Superintendent to become a living, mobile ‘Vergil’.

Those who were violent in life were kept in the seventh circle of hell, depicted in Inferno as a desert continuously ignited by falling sparks or cinders. Fittingly, it has begun to rain as Sadie begins Circle 7, and Mike will shortly suit her up for battle, worried she might be shot. His fears are justified: they encounter Marshall Glick, a violent ex-police officer who is murdering his former co-workers. The seventh circle of hell is also home to suicides, however, and Marshall effectively kills himself by taking on an entire SWAT team. By contrast, in this same Circle, Dr Endesha describes the new aliens, the Engineers, as being “inquisitive, not violent” [emphasis added], and reveals that he and Vergil are learning to speak with the creatures – yet another example of attempted communication. These attempts are halted by Kinsler, who viciously pulls the plug on Vergil, shutting down the city in the process.

Circle 8 is packed with almost as many references to communication as the other audio logs combined. Taking place on the fourteenth floor of the police building – Emergency Comms – this Circle focuses on what is effectively both New Mombasa’s emergency services hub and its propaganda division; the latter is particularly fitting when we remember the eight circle of hell holds those guilty of fraud and falsification. There is a surprising amount of information compressed into a few lines of background chatter as Sadie and Mike enter, the most pertinent being the argument the duty officer is having via chatter (read: telephone) with one Captain Dare about the Superintendent being powered down. Sadie fails to convince anyone that the stapler she is holding in her pocket is a gun (a kind of fraud), but finally she and Mike succeed in persuading the duty officer to nonetheless switch the Superintendent back on. (There are heavy suggestions from now on that Vergil has merged with the freed Engineer from Circle 6, Arc 2, although this will not be confirmed, as such, until later in the game proper.)

Next, Mike tracks down and confronts Stephen, of the “Public Service Announcements Division”, regarding his triumphal propaganda, which is woefully out-of-step with the situation on the ground. “None of it is true,” says Mike, but when Stephen presents him with the opportunity to speak his mind on the air, Branley backs down, offering only lame platitudes in place of Stephen’s fraudulent rhetoric; although well-intentioned, he turns out to be just as guilty of deception.

The ninth and final circle of hell is reserved for traitors, who are encased to differing depths in a lake of ice called Cocytus, kept frozen by the flapping of Lucifer’s wings. In Circle 9 of ‘Sadie’s Story’, this lake of ice is replaced with argon, as Kinsler breaks an earlier promise to Sadie and freezes the Data Hive with her father still inside. She discovers this when she meets him on platform nine of Kikowani Station (which we will later visit as Buck, with the ODSTs close to reunited). Sadie asks Kinsler if he ever worries that there might really be a hell; he answers that he knows there is, and they are leaving it. In truth, however, they are now reaching its very depths. Kinsler’s corrupt cops betray the people they are meant to protect by firing on a crowd of refugees, and Kinsler reveals what would have been the greatest treachery of all: his efforts to capture the Vergil Engineer (which he calls “a pink, airborne octopus”). Kinsler believes that securing the alien will confer upon him the status of hero, when in fact Vergil is Dare’s primary objective and vital to the war effort. Ultimately, Kinsler receives a similar punishment to that of Judas Iscariot (whom Dante considered the traitor above all others), albeit torn apart by an angry mob rather than gouged by the teeth of Satan himself.

Sadie is forced to flee the city with Mike, leaving Vergil, her saviour, behind. When Sadie asks who will rescue him, Vergil responds with a sequence of voice snippets lifted from her adventures throughout ‘Sadie’s Story’. First, in the voice of the Emergency Comms duty officer, he answers her, “Office of Naval Intelligence”, then sputters out, “Your tax dollars at work!”, before ending with Stephen’s words: “Fallen heroes – on the air.” The heroes Vergil is referring to have not fallen quite yet, but they will, and on the orders of one Captain Dare of ONI; the Rookie will be among them. The audio logs finish as they began, with the sounds of a train heading for Hope Station … and beyond: we are rediscovering hope, having left it behind; these things, after all, are circular.

6. A Corrupted Signal

So ‘Sadie’s Story’ serves both as insight into the life of New Mombasa before our arrival and as an intertextual work that further highlights the game’s thematic intricacy. But what of it? On the first point, an audio story alone cannot suffice to excuse the sterility of New Mombasa as we traverse it in the game proper. And while such sterility is understandable given the constraints placed on the development of ODST, we shouldn’t forget that a similar barrenness abounds in Bungie’s previous depictions of life on Earth, in titles that had more time and resources dedicated to them. Additionally, we have to admit that some of the better storytelling in a Halo game has once again become peripheral to the machinations of the main plot.

There are some positives to consider, however. While most players won’t track down every last audio log in ODST (a not inconsiderable task) and so will never hear the conclusion of ‘Sadie’s Story’, it is unlikely that anyone could avoid stumbling over even a few logs, and so will receive – if they are prepared to listen – some small insight into the life of New Mombasa prior to their arrival. More importantly, the “main plot” of ODST is relatively nimble when contrasted with the cumbersome space opera of the other Halo games, and ‘Sadie’s Story’ works to reinforce its smaller, more human concerns. There exists a better harmony between this game and its story elements than in any other Halo title, suggesting Bungie have become more adept at their combination. And for those players who do locate every log, there occurs an event in-game that serves both as reward and resolution.

Concerning the second point above, namely the intertextuality between ‘Sadie’s Story’ and Dante’s Inferno … well, why should we care? For at least two reasons. First of all, it demonstrates that Bungie are conscious and aware of their story’s worth, of what it says, of what the tone is and should be. It shows us that ODST represents a deliberate effort, at every level, to craft an ostensibly smaller story about human concerns, namely our experience of isolation, and the ways we can overcome it (through good communication, camaraderie, and even love). Second, it lends greater weight to the events of ODST. In tying their story to a masterpiece of religious poetry, Bungie are suggesting that the same themes inform both works. Inferno may be the best known part of The Divine Comedy, but it is exactly that, a part, and Dante later goes on to tour purgatory and heaven itself. Ultimately, he comes to an understanding of the unity of God’s loving creation, despite the horrors and punishments he witnessed in hell. Vergil’s guidance through the first two-thirds of the poem helps Dante to find the diritta via again, to be consoled; passage through Inferno is only a necessary trial toward that good end. In Halo 3: ODST, a very different Vergil likewise guides the Rookie through the lonely hell of an occupied New Mombasa, and eventually helps all of the ODSTs and Dare to escape the city together. They do so with an increased unity and sense of purpose, and the shared experience even reignites the long-dormant relationship between Buck and Dare.

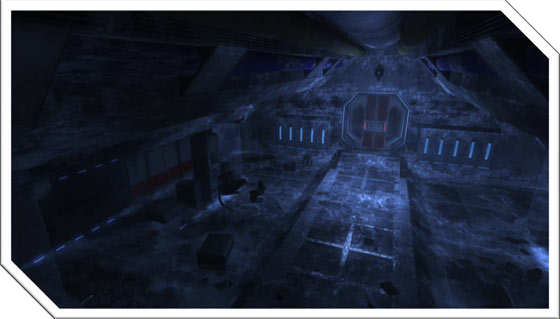

Before this can happen, however, the Rookie is required to negotiate the very depths of New Mombasa, at the game’s geographical and thematic nadir. Having navigated the city, he has successfully ‘solved’ the mystery of what happened to his squad (in the final flashback, at Kikowani Station, we learn they have fled New Mombasa in a hijacked Covenant Phantom, believing the Rookie and Dare to be lost or dead), and now he realizes he has been left behind, that no help is coming. The dread silence is broken by the interception of a communications signal from Dare, who is miraculously still alive, albeit trapped on sub-level 9 of the Data Hive below the city. The Rookie, with no other course of action available, takes it upon himself to make the descent, zipping down an elevator shaft into the very bowels of New Mombasa. In keeping with Bungie’s numerical obsession, this takes him only as far as the seventh level.

It is at this point that the main narrative of ODST dovetails with ‘Sadie’s Story’, as the Rookie encounters a police officer who shares his interest in reaching sub-level 9. The officer’s passage until now has been halted by the city Superintendent, but the Rookie’s arrival prompts Vergil to raise the data-stacks that were blocking the way. This act is accompanied by a veiled warning about our new companion: “Warning! Hitchhikers may be escaped convicts!” As it turns out, the police officer is one of Kinsler’s corrupt cops, sent to clean up any loose ends surrounding the murder of Dr Endesha. As revealed in ‘Sadie’s Story’, Kinsler had previously released argon into the Data Hive, deliberately freezing it and thus killing Sadie’s father. Provided we have found all of the audio logs, the police officer leads us right to the site of Endesha’s death (Vergil helpfully chirps, “Crime scene – restricted entry.”). Here the cop turns on the player and forces us to kill him. “Good citizens do their part,” comments Vergil approvingly, as the officer falls dead not a few feet from the hunched corpse of Sadie’s father. The room around us is a deep, dark, chilling blue. This is sub-level 9, the icy Cocytus of Dante’s Inferno, and the emotional core of Halo 3: ODST. We have come closer to Dr Endesha than Sadie managed over the course of all her audio logs, and yet there is nothing we can do to resurrect him, or her – unless we wish to play the tapes over and listen again to their painful separation. The Rookie, and the players who control him, have been the audience to a drama – a short, sideline drama, but a drama nonetheless – that unfolded with a degree of intimacy never before seen in a Halo game. It is a worthwhile, wholly felt moment, and one that takes place solely in our first person view, without the Rookie ever saying a word.

The rest of the game is concerned with our escape from this, the lowest point. We reunite with Dare, who is surprised but also relieved to see us, and venture together through the Data Hive to find Vergil, who is now revealed to have merged with the rogue Engineer of ‘Sadie’s Story’, so becoming a crucial source of intelligence for the UNSC. The Covenant arrive, trying to retrieve Vergil by force, but our heroes manage to escape to the surface with the aid of Buck – who could not forget his obligation to Dare, to Veronica, and so has returned for her. The four principals – Buck, Dare, the Rookie, and Vergil – rise to the surface in another elevator. This ride is remarkable for its warmth and sentiment, with Buck and Dare embracing while the Rookie and Vergil exchange a silent but telling glance; at last, they are attuned and communicating. On the surface, we discover morning has broken and the skies are clear: the night’s oppressive bad weather has been dispelled, and we are no longer trapped in darkness. When we reach the coastal highway that will serve as an escape route, it is with New Mombasa’s sinister copse of skyscrapers at our backs, to the west. Ahead, in the east, is the rising sun. We drive toward it. The highway is a circle, of course, looping around the high walls and water of the ONI Alpha Site, and our ultimate escape is made via the enemy Phantom the ODSTs liberated earlier (at the risk of another unwarranted stretch, it is worth noting that Dante and Vergil make use of Satan’s own back to clamber out of hell). Finally, we ascend from New Mombasa.

Buck can’t resist a final parting hint on Bungie’s behalf (“What can I say? It was a hell of a night.”), but it is the injured Romeo’s closing remarks that are the most telling. “We went through hell for that?” he snickers, and the remark is double-edged, as he is talking not only about the alien Vergil, but also the romance flourishing once again between his sergeant and Dare. To answer Romeo’s question: yes, on both fronts. We suffered through that night in New Mombasa superficially for Vergil’s intelligence, which is somehow vital to the war effort (and presumably to the main plot of the Halo universe), but more importantly for the sake of our squad mates, and a shared experience of human loneliness. In a sense, then, the ODSTs went through hell for one another, overcoming problems of communication, limited resources, and convolutions of plot – just as Bungie seem to have done in this, the best-written instalment in their series of Halo games to date.

7. … and Beyond

When evaluating Halo 3: ODST, we should remember that it’s the first of Bungie’s Halo titles to feature a map. It is the first game that has needed one. After all, the navigation of New Mombasa is central not only to the gameplay, but to a story in which we are searching for beacons, for our lost squad mates, for a safe route out of an occupied city. There is a refreshingly new unity between the aspirations of Bungie’s designers and the actual experience of playing their game. In this and several other crucial respects, ODST offers us storytelling that is far more successful than that of the predecessors, and even showcases Bungie’s newfound ability to weave game and world. In light of this, the disappointments are slight: the members of the squad often struggle to defy their set archetypes (and much of their dialogue is trite), while the same environmental problems of sterility and repetition are just as present in ODST as in the trilogy proper. Here, however, they serve in part to reinforce the player’s singular experience of New Mombasa; and while there still exists a gulf between the purported extinction of a galactic “humanity” and the game we end up playing, it feels narrower than before: not every player will take the time to reveal all of ‘Sadie’s Story’, but even the most casual will likely stumble upon a few logs, and hear real people recorded therein – speaking, pleading, crying. Best of all, Bungie have lovingly sketched a cast of characters whom we can remember fondly not just for their combat banter, but for their closeness, their consistency, and – briefly, in flashes – their human feeling. When you consider that ODST was a one-year project from a small team, its flaws become less glaring, and the promise of Halo: Reach, their next full-blooded game, becomes considerable. We should leave New Mombasa, as the Rookie does, looking up.

Shake Appeal

You not going to believe this but I have lost all day searching for some articles about this. I wish I knew of this site earlier, it was a fantastic read and really helped me out. Have a good one

I didnt know ODST was so deep

At the end of my journey to find all of the audio logs, I had realized that there might have been the connection of the back story to Dante’s Inferno when I followed the cop into sub-level 9’s frozen depths. After killing the cop, I was like, “wow.”

Thanks for writing the article, as it did reinforce my understanding that there was the connection to Inferno in ODST.

It is amazing that this article was published, because i was thinking about putting a forum of this analysis on Bungie’s website, but i see it’s already been done here, but ODST was an amazing allegory or interpretation of Dante’s inferno, and the superintendent name is even virgil.

The police/Brooks/Murdoch saga gets ever more labyrinthine. It’s now come out that the police lent her a horse! You know, as you would LOL! One hopes she didn’t look this gift in the mouth! Not that all these people were close or anything. It seems the horse is dead now – does this mean its head has turned up on someone’s pillow somewhere?

[url=http://www.dieselsalejp.com/]????? ??[/url]

[url=http://www.guccibagstepo.com/products_all.html]GUCCI ???[/url]

[url=http://www.guccibagsjpbagu.com/]??? ?? ??[/url]

Even in 2019, this is a fantastic read. Well written and made me appreciate ODST all the more. I played through it recently. It still holds up. I’m hoping the author of this article enjoyed Reach. There are quite a few humanizing moments in it, be it the farmers, the lone survivor of Covenant assault, or an entire level built around protecting an evacuating city.